Harvey Pynn / Consultant in Emergency Medicine / Medical Director of WMT

Dr Harvey Pynn is a Consultant in Emergency Medicine at Bristol Royal Infirmary, Honorary Consultant in Pre-Hospital Emergency Care with the Great Western Air Ambulance and Medical Director of Wilderness Medical Training. With an expansive array of expedition experience across mountain, desert and jungle, he knows his stuff when it comes to planning for and dealing with medical problems in the wilderness. Adventure Medic is proud to present to you Dr Pynn’s pearls of wisdom for well-prepared expedition medics. Take note.

In remote environments, alone and miles from higher echelons of medical care, with no tests, expensive investigations or treatments to fall back on, medical care relies on clinical acumen, lateral thinking and improvisation. Before putting yourself in such an environment, why not hone your trade and gather some new skills to equip yourself for the trip ahead.

Six months experience in emergency medicine is often essential prior to embarking on any wilderness expedition as the medic, but failing that, why not join a course or conference such as those run by Wilderness Medical Training (Chamonix, Morocco or the UK) to develop the necessary skills and much more besides.

I’ve put together a list of helpful hints that will stand you in good stead to be the medic on an expedition. The first few are generic qualities that will make you an attractive proposition to an expedition leader. The remainder are, in my experience, the top skills you need to master in order to be able to confidently deal with the most common injuries and ailments on an expedition.

Words of advice

Be able to look after yourself and understand your environment

Be able to put up your basha in the trees if you’re going to the jungle, be able to dig a snow hole if you’re going to the mountains, be able to navigate using a map and compass and be able to set up and use a radio, GPS or satellite phone. Being a medic on a trip is a privilege but remember you are also a member of the team and as such, must have other skills to bring to the party.

Get to know your team before you go

An evening get-together or weekend away can be more valuable than a pre-travel medical questionnaire sent in the post. You will glean a great deal of information from team members as well as observing team dynamics. With developments in the transport industry and a boom in interest in adventure travel, remote destinations are becoming more accessible to the general public. Subsequently, pre-existing health problems amongst wilderness travellers are becoming more common. Be aware of these and seek practical specialist advice from doctors who understand the rigours of expeditions. A list of Diploma in Mountain Medicine (DiMM) holders can be found at www.medex.org.uk. A travel and expedition history should be an important part of your history taking – someone with diabetes who has travelled with success to altitude before is likely to cause far fewer problems than an arthritic who has done their pre-expedition training on a treadmill in the local gym.

Know where to look for resources

The National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC) is a UK Government sponsored organisation that has a comprehensive website for healthcare professionals, giving up-to-date information on all matters of travel medicine. The Health Protection Agency (HPA) also provides useful resources, such as malaria prevention guidance for travellers and rabies post-exposure prophylaxis guidelines. There are also lots of useful links listed in the Adventure Medic Resources Section.

Top ten medical skills to master

1. Understand the importance of the respiratory rate

Always measure it accurately in illness or injury. It is the first physiological parameter to alter. Doctors are notoriously poor at measuring or documenting it correctly. Omit it at your peril! Dyspnoea points to a respiratory problem, whereas a tachypnoea may point to a metabolic issue. For the doctors out there, there will be no nurse to rely on so get accustomed to completing an observation chart to look for trends.

2. Know some basic ophthalmology: revise the anatomy and how to examine an eye

- Always check visual acuity and beware those who report a significant reduction in their visual acuity.

- Know the difference between the conjunctiva and cornea.

- Know how to instil local anaesthetic eye drops and fluorescein to look for corneal defects under blue light – know the difference between an abrasion and a dendritic ulcer

- Know how to evert the upper eyelid to check for a foreign body

- Practice removing a foreign body with a cotton wool bud.

- Beware contact lens wearers on an expedition – they are prone to development of corneal ulcers (ulcerative keratitis) that can be sight threatening if overlying the visual axis and not addressed immediately.

- Remember a ‘lost’ contact lens usually finds its way to the upper outer quadrant.

- Ointments are preferable to drops in an expedition setting.

3. Know how to ‘clear’ a neck

Fracturing the cervical spine requires significant force. Not all patients need to have their cervical spine immobilised. Remember having an immobilised neck will require a patient to be log-rolled and evacuated by stretcher, utilising considerable resources. Know the Canadian C-spine rules and NEXUS guidelines to help you decide whether you can ‘clear’ the neck without having to resort to immobilisation and imaging.

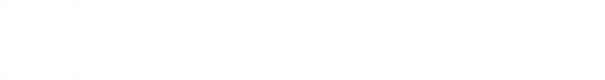

4. Revise the Ottawa ankle rules

Soft tissue injuries are common on an expedition. Of these, inversion injuries of the ankle are the most common. Knowing the Ottawa ankle and foot rules will allow you to exclude a significant fracture and treat the injury as a sprain. The most common tissue injured in an inversion injury is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) complex on the anterolateral aspect of the foot.

5. Know how to strap a sprained ankle using zinc oxide tape

- Place an anchor strap around the mid shin (not completely circumferentially) and around the forefoot

- Place a stirrup strapping around the foot with the foot placed in very slight eversion if an inversion injury.

- Add support strapping over the ATFL complex (3 strips of tape) and secure the stirrup by placing a ‘locking’ strip of tape.

- It may be appropriate to add a further stability figure of eight strap around the heel depending on how secure the ankle feels to the patient.

- The zinc oxide tape will lose its tension and so will need to be replaced every day.

- Hint – shave hairy legs before applying strapping for comfort and also to prevent minor trauma and risk of folliculitis.

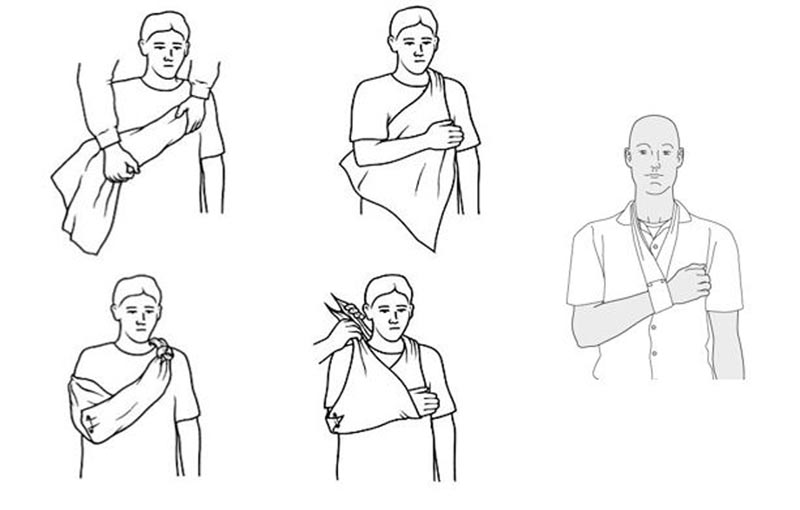

6. Know how to apply a high arm and a broad arm sling and the indications for each

- High arm slings are applied for hand injuries to enable swelling to reduce.

- Broad arm slings are used to maintain comfort in forearm, shoulder and clavicle injuries.

- For fractures of the humerus, a collar and cuff is a more appropriate method of splintage.

7. Know how to prevent and treat travellers’ diarrhoea

The majority of travellers to wilderness settings will be afflicted by a diarrhoeal illness. Educating on preventative measures is the responsibility of the medic. You should emphasise the importance of rigorous hand washing, filtration and purification of water, avoidance of uncooked or unpeeled food (particularly salads) and ice in drinks.

- In the event of persistent diarrhoea (>24 hours), prescribe a stat dose of ciprofloxacin (500 mg – caution in athletes) or a short course of azithromycin (500mg od for 3/7 – if in Asia).

- The presence of blood in the stool is suggestive of colitis, which if infective, will need a longer course of antibiotics.

- Loperamide (or similar) can be used (2mg after each loose stool) but be aware of the risks of ileus.

8. Learn some basic dentistry

Dental treatment falls outside the remit of the majority of practising doctors. Everyone should have a dental check-up and preferably an x-ray of their teeth before travelling but toothache is still common despite the best laid plans. Persistent pulsing pain, often in response to thermal stimuli is a sign of irreversible pulpitis, whilst tenderness of the affected tooth suggests periodontitis. In either case, examine the teeth under good light. A previous filling may be loose or there may be a new hole or crack in the enamel of a tooth. All expedition medical kits should contain a rudimentary temporary filling kit. Ensure the tooth is a dry as possible (use a cotton wool bud to dry the tooth) and know how to apply a small amount of filling to seal any defect to enable the patient comfort whilst a more permanent dental solution is sought. If a tooth abscess develops, treat with amoxicillin and metronidazole and be aware of the signs of Ludwig’s angina. (See also Adventure Medic’s Guide to Expedition Dentistry for more information.)

9. Take good care of feet

On an expedition, foot problems can curtail the trip. It may be necessary to do foot inspections regularly.

- Prevent blisters by ensuring everyone has suitable worn-in footwear.

- If people are prone to blisters, use zinc oxide tape to protect those areas of the feet.

- If hot spots develop during activity, stop and tape up affected areas before blisters occur.

- If blisters do form, use a sterile needle to decompress them, spray the area with antiseptic and apply zinc oxide tape. Once applied, do not remove it and allow it to fall off when the underlying skin has healed -continuous removal and reapplication of tape will lead to further trauma and risk of infection.

- Ensure people change their socks regularly and powder their feet with an antifungal foot powder twice a day especially in humid environments.

- Check that everyone knows how to cut their toe nails to reduce the chance of ingrowing toenails developing – the nail should be cut level rather than dome shaped. In the event of an ingrowing toenail, know how to perform a wedge excision under local anaesthetic ring block.

10. Know how to give an intramuscular injection

Those of us working in hospital medicine rarely use this mode of drug delivery. Don’t forget the benefits of this in an expedition settings – anti-emetics and analgesics are the most common drugs to be delivered in this manner. Bioavailability and speed of onset are excellent if administered into the deltoid muscle. Become re-accustomed with this skill by asking a nurse or GP to remind you of the do’s and don’ts.

A final thought…

Finally, keep in mind that road traffic accidents are the most common cause of death in travellers. Do a risk assessment on vehicles and drivers before you eagerly leap aboard. Make sure someone in the group is awake at all times and have in your mind what your actions will be in the event of an accident.